A day has come to acknowledge and honor those who served in the Vietnam War, including the 58,479 Americans who never made it home. Join us on March 29 at 11 a.m. in the courtyard behind City Hall as we remember those who were called and served in the Vietnam War.

March 29 marks the day in 1973 when the last U.S. combat troops left Vietnam. For those of us who were there, those memories will never fade.

I was just 19. I grew up on the Jersey Shore, surfing and racing my '56 Chevy. The day I shipped out, my father—a World War II combat medic wounded on Iwo Jima, Tinian, and Saipan—drove me to the airport. A man who had seen hell and never cried was sobbing as I walked away.

At Travis Air Force Base, I spent three days in a barracks without air conditioning, sweating in 100-degree heat. When we landed in Saigon, the air smelled of fish heads and rice. A bus took us to the Annapolis Hotel, where we were told to keep an eye out for anyone attaching a bomb to the bus. I got my first security watch that night, from midnight to 4 a.m. They handed me a plastic M-16, a so-called "Mattel toy gun." I had never seen one before.

The next morning, I turned on the news. There was a riot. Then I saw the caption: Asbury Park, New Jersey—my hometown. Days later, when mail caught up to me, I learned my father had been the Incident Commander for the fire response. He had pulled his crews back after the truck he was standing next to came under fire.

"Toto, We're Not in Kansas Anymore"

The next day, I stepped outside, hoping to find a French restaurant I'd heard about. A young boy on a Honda 50 zipped past a U.S. soldier, grabbed his watch, and took off. A White Mice police officer—the South Vietnamese police force—fired a single shot, killing both boys. The soldier calmly picked up his watch and kept walking. He had been here too long.

I looked down at the short-timer calendar someone gave me. It was a picture of a woman, her body divided into 365 squares. I shaded in four days. I had 361 left.

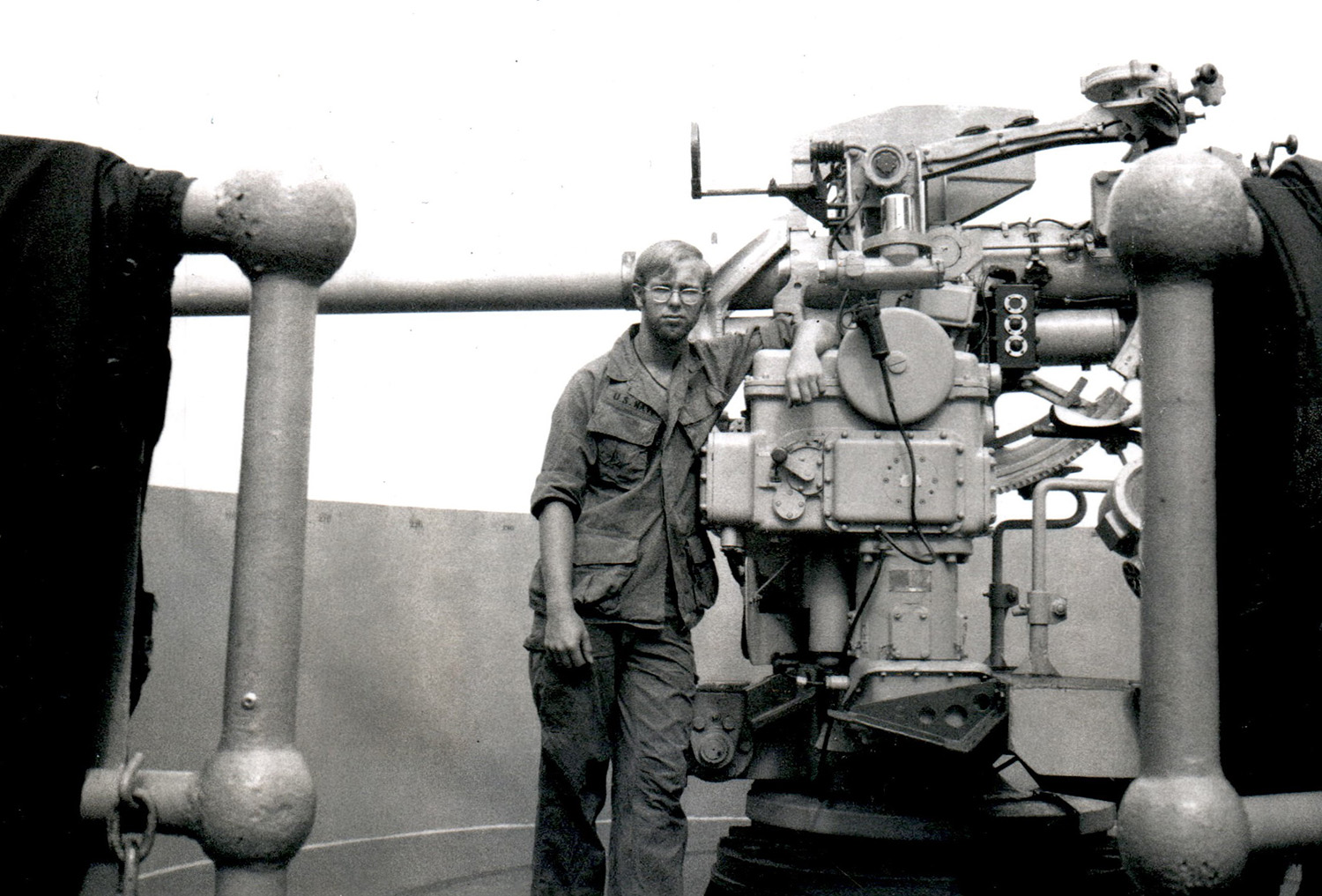

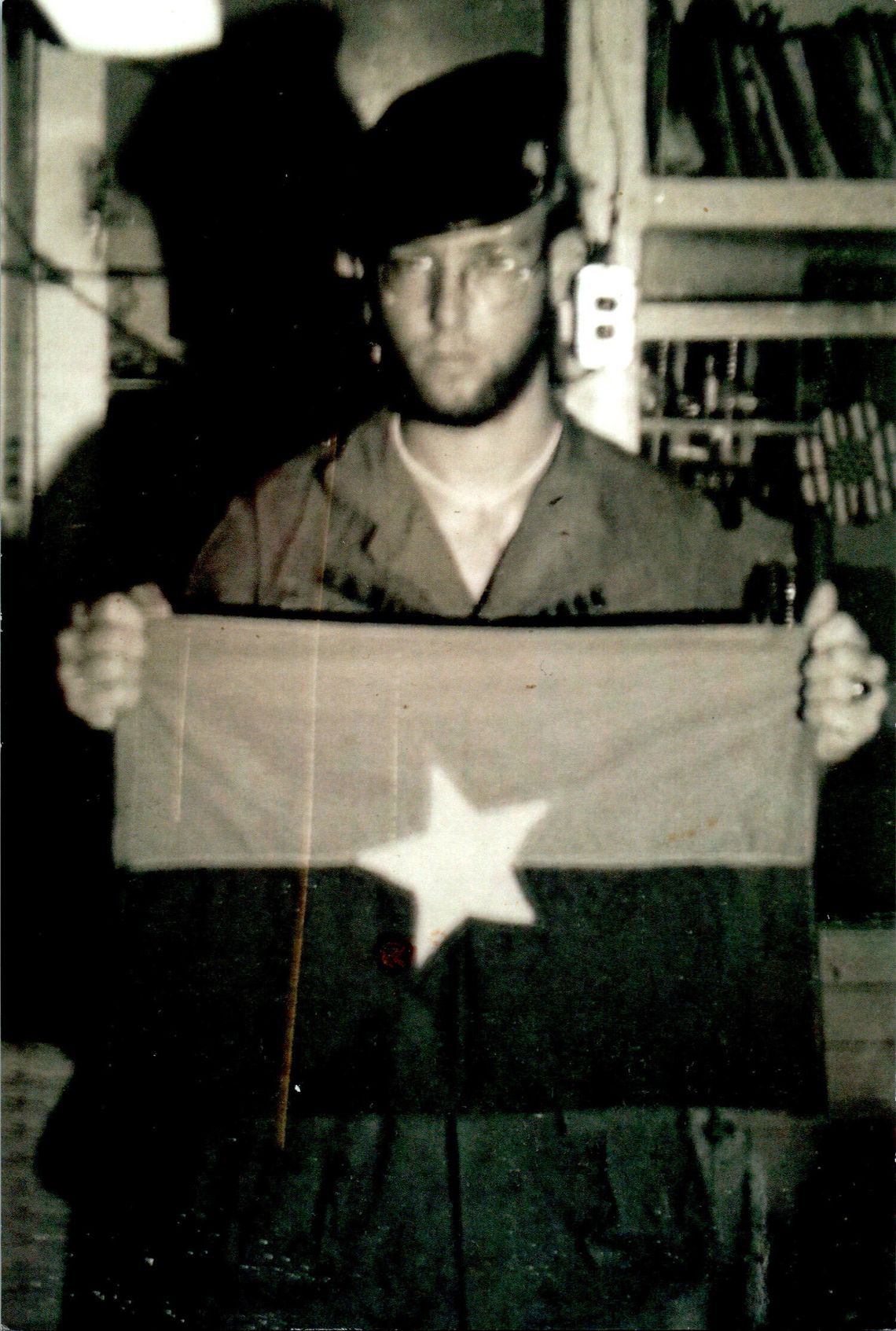

Soon, I was headed to Nha Be, sweeping for mines in the Saigon River to keep supply freighters safe. Our 56-foot boat, classified as a Minesweeper River, was loaded with firepower—three .50 caliber machine guns, an M-60, an M-79 grenade launcher, and two M-16s. When we weren't clearing mines, we were a gunboat, a troop carrier, a supply runner. When things got rough, we called for Seawolves (Huey helicopters) and Black Ponies (OV-10 attack planes).

"Who Gives a 19-Year-Old a .50 Cal?"

I manned a .50-caliber machine gun—something I never imagined doing. I also had to teach Vietnamese sailors how to operate the boat's twin 6-71 Detroit Diesel engines. They had only ever plowed rice fields with water buffalo. There were no Vietnamese words for the things I needed to teach them.

We were kids, really. I don't think people back home understood what it meant to be 19 years old and responsible for weapons and machinery that could take lives. Some days, it felt like we were just trying to survive until the next mail call, marking off the days on a calendar we weren't sure we'd finish.

Our hero on the rivers was James E. Williams, a boatswain's mate and Medal of Honor recipient. On October 31, 1966, he led two Patrol Boat Rivers into an ambush, taking on dozens of Viet Cong sampans. He and his crew killed nearly 1,000 enemy combatants and destroyed over 50 boats. He was the most decorated enlisted sailor in U.S. Navy history.

"The War Didn't End When I Got Home"

A month before I was set to leave, I got a Dear John letter from my girlfriend. Along with my high school photos and souvenirs, she was gone. So were my friends. The same people who threw me a going-away party had turned against me. I was spit on in the airport when I came home.

I don't go back to my hometown. The same hatred I saw in the '70s, I see in today's universities.

We didn't lose that war—the politicians did. Our hands were tied by rules of engagement designed to "protect civilians" but cost American lives instead.

My boat captain had it right. When he requested permission to fire, he said, "If I don't hear that .50 barking, something's wrong."

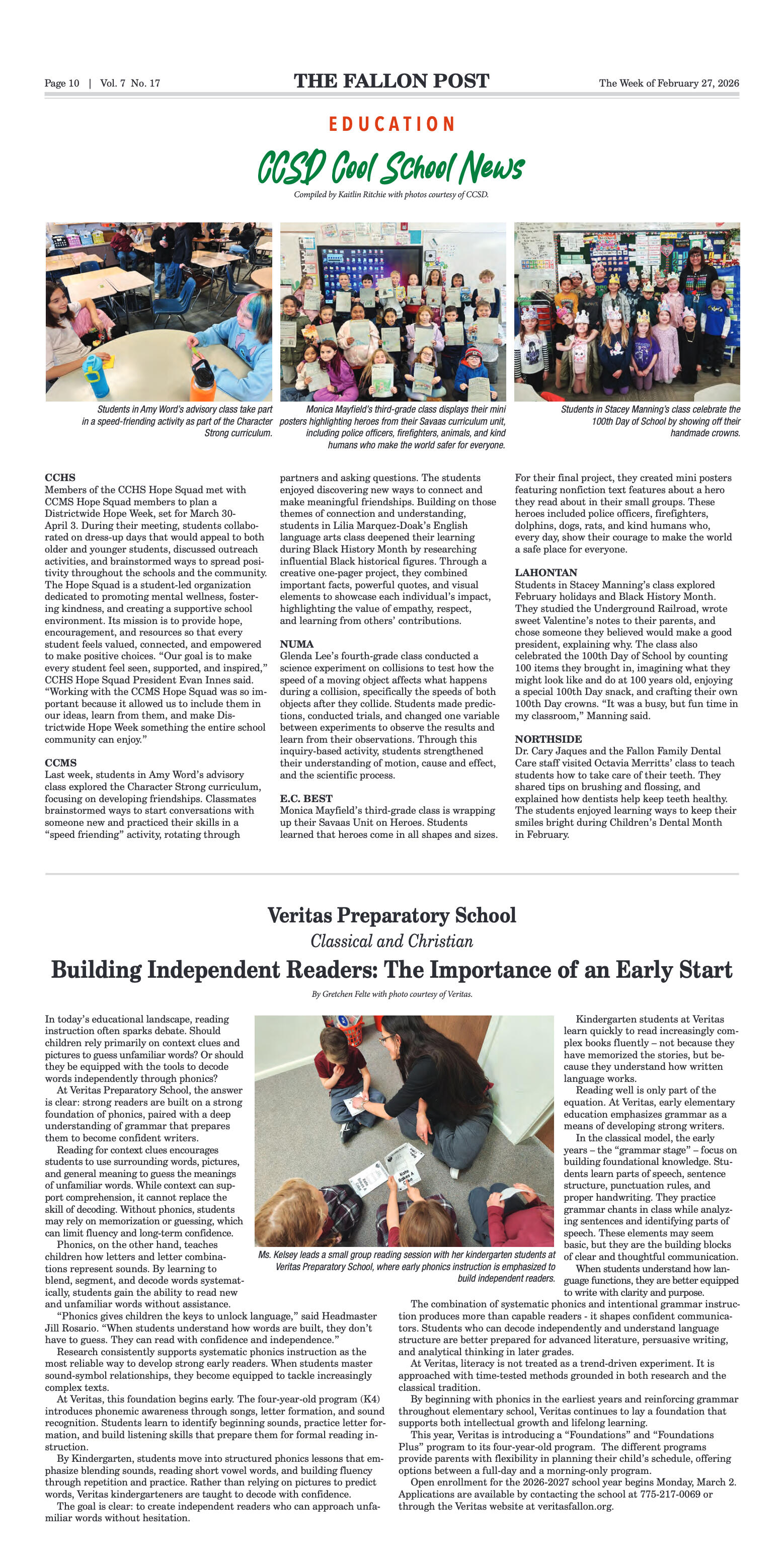

I stayed in the Navy for 10 years, making Chief Petty Officer in eight—but I walked away to become a federal firefighter. I spent the rest of my career protecting those who protect our nation, rising to Fire Chief at NAS Fallon. Photo :I wanted to take this apart and mount it on our ship. Photos courtesy of Stuart Cook.

"March 29: A Day to Remember"

I tell my story not for sympathy but so people understand.

I never want another generation of veterans to experience what we did. But when I see today's troops welcomed home with cheers, flags, and handshakes, I can't help but feel it's too late for us.

The war never really ended for us. It followed us home in ways most people will never understand. It was in the looks of people who used to be our friends, in the silence at the dinner table when we tried to talk about what happened, in the nightmares that never went away.

On March 29, 2025, fly the American and POW/MIA flags. Remember those who never made it back. And, if this country ever sends another generation to war, let's do it differently—better. Let's support them, stand behind them, and let them win.

God bless our veterans. Welcome home, brothers.

Comment

Comments