Slumgullion, Then, Later, and Now

Several years ago, my oldest daughter, Kelli Kelly, asked me to write an article about one of my favorite dishes. I deferred at that time because I was in the process of writing my first novel, Identity – (Dream Maker), available from Amazon.com in both paperback and on Kindle. In the interim, Kelli has authored many pieces for The Fallon Post. I am in between projects today, and with the outside temperatures to reach 90+ for the second day, I decided to dust off my Slumgullion recipe.

Slumgullion: Then

Slumgullion may not sound like the most appetizing name for a dish, but that’s part of its charm. The word’s etymology doesn’t do it any favors: “slumgullion” is believed to be derived from “slum,” an old word for “slime,” and “gullion,” an English dialectical term for “mud” or “cesspool.” Most of the earliest recorded usages of “slumgullion,” such as in Mark Twain’s Roughing It (1872), refer not to a stew but a beverage. The sense referring to the stew debuted about two decades later, and while there is no consensus on exactly what kinds of ingredients are found in it, that’s the “slumgullion” that lives on today.

A variety of cultures lay claim to the name ‘Slumgullion’; English, Irish, Pirates, Pioneers, and many more. Some folks have negative associations with it. ‘Slumgullion’ denoted fish offal of any kind. It also meant “the watery refuse, mixed with blood and oil, which drains from blubber. Later, ‘slumgullion’ was the name for the muddy deposits at a mining sluice. And finally, it came to mean “a kind of watery hash or stew. In 2013, a visiting friend from the United Kingdom (Paul W.) described an ‘If It’s Stew’ that his mom makes. “Basically, if it’s in the refrigerator, it goes into the mix,” he said. By all accounts, Slumgullion Stew falls into the category of a ‘clean-out-the-refrigerator,’ ‘everything-but-the-kitchen-sink’ type of meal.

I had my first Slumgullion in the early 1960s. I was on my way home from a successful grouse hunting trip in an old abandoned homestead’s apple orchard about 2 miles from my home in the Cascade foothills of northwestern Washington State. I was carrying a shotgun and following the Great Northern railroad tracks that were close to the orchard and my home. The railroad serviced the cement plant where my dad worked, delivering limestone and hauling away the finished cement product. Frequently there were unauthorized “passengers” on the freight trains that stopped to service the cement plant. These “passengers” would hop off the train and go to a small camp near the tracks to respond to Mother Nature’s call, obtain fresh water, and start a fire to cook up a meal.

These passengers would also walk into our little 30-house “town” to see if they could scare up some food they could put into the common kettle. What went into the kettle were cans of beans, corn, and whatever they had from their individual stashes, plus what they could forage from gardens in town or what they could obtain from the residents. My mom would pull small amounts of garden vegetables for our visitors. Depending on what was available, the visitors might leave with potatoes, onions, carrots, beets, radishes, lettuce, corn, etc. Mom’s garden was extremely large and continuously worked by one of her ten kids and always had plenty of produce for the family and others. Mom would also supply sandwiches and cookies if available. We had a mark placed on our fence corner that indicated that “a friend lives here.”

Hobos have played a big part in the history of America – one that’s often ignored. They were the nomadic workers who roamed the country at the start of the 20th century and through the Great Depression, taking work wherever they could and never spending too long in any one place. In their extensive travels, hobos learned to leave notes for each other, giving information on the best places to camp or find a meal or dangers ahead. This unique Hobo Code was known to the brotherhood of freight train riders and used by all to keep the community of traveling workers safe, fed, and at work—first, a bit of history. Today, the word hobo is often used interchangeably with “bum” or “drifter,” but hobos were a specific type of homeless traveler. Hobos traveled around for the sole purpose of finding work in every new town they visited, having usually been forced from their homes by the lack of jobs there. Bums avoided work in favor of drinking heavily, and “tramps” only worked when it was absolutely necessary.

Because of their willingness to take the jobs that no one else wanted – and the fact that they followed a strict moral code – hobos were tolerated by some. Regardless, life as a hobo was difficult and dangerous. To help each other out, these vagabonds developed their own secret language to direct other hobos to food, water, or work – or away from dangerous situations. The Hobo Code helped add a small element of safety when traveling to new places.

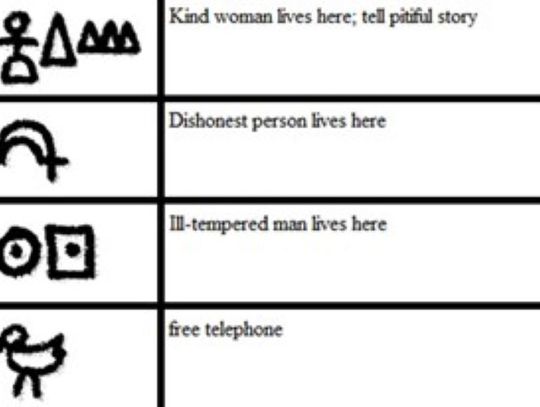

The pictographic Hobo Code is a fascinating system of symbols understood among the hobo community. Because hobos weren’t typically welcomed (and were often illiterate), messages left for others in the community had to be easy for hobos to read but look like little more than random markings to everyone else to maintain an element of secrecy. The code features certain elements that appear in more than one symbol, such as the circles and arrows that make up the directional symbols. Hash marks or crossed lines usually meant danger in some form. (See image below)

On my return from the hunting trip, I came upon the camp where the hobos were preparing their meal and was invited to join and share their meal while, at the same time, they were eyeing the grouse that I was carrying. As I was warned, “If you treat them nice, they will treat you nice,” I agreed to share their and my food and gave them my birds to add to the dinner. I was amazed at how quickly the grouse feathers were removed, the grouse cleaned, and on a spit over the fire. At no time did I feel threatened? That was my first exposure to what they called “slumgullion.”

Slumgullion: Later

Fast forward to the mid-1990’s1990s. I lived alone in Yorba Linda, California, trying to conserve money and save for retirement. My two daughters would visit, and rather than go out to dinner, I would cook something they enjoyed. One day, I decided to make a newer form of “slumgullion,” I was surprised to learn that both girls liked it. I started out by chopping up a medium-sized sweet onion and 3 or 4 cloves of garlic (depending on the size and taste of those targeted for the meal). I added these to a frying pan and some vegetable oil and started softening/browning. While the onions/garlic were frying, I took two large russet potatoes that I peeled and cut into ½-inch cubes that I added to the frying pan, ensuring that there was an adequate amount of vegetable oil, and adjusted the heat to medium heat to avoid burning. In a separate pan, I browned 1 pound of hamburger meat. When the hamburger was adequately browned, I drained the fat off in a strainer and then put the hamburger back into the frying pan. By this time, the potato mix was browned.

I drained the remaining oil, patted the potatoes dry with a paper towel, and added this to the hamburger, placing this mix on low heat. Then, I attacked the leftovers in the refrigerator. Often I would add leftover corn, peas, beans, chili, or whatever else was not growing hair to the mix. If I knew that I would be making Slumgullion, I would have some mushrooms available to be chopped and added to the mix. If the pan looked like it would burn, I would add small dollops of butter to keep the mix heating rather than burning. Our favorite version of this gullion was when we had little or no leftovers to add. I would peel and chop up several Patty Pan (Silver Dollar) squashes and add this to the mix. Covering the pan would keep the liquids in place and cook the squash.

When I served this gullion, I would offer pepper and catsup for seasoning/flavoring to the girls while I might add hot sauce for my dining pleasure.

I made this dinner often enough, which probably helped me balloon to 260 pounds. This meal was served to my daughters quite often, and I believe it was the impetus for Kelli to attend the San Diego Culinary Institute to learn about alternatives to my cooking. Ultimately, I credit Slumgullion with Kelli’s column in the Fallon Post.

Slumgullion: Now

After I suffered a minor stroke, I had to drop Slumgullion from my regular meals. After switching to significantly more exercise and a healthier diet, while not stopping me from having a heart attack and resultant angioplasty and stent, I dropped 70 lbs. Recently I started with a new “Keto-leaning” Slumgullion that I make about once every two weeks.

This recipe makes a large amount of Slumgullion that, when paired with a vegetable such as avocado slices or steamed (zucchini, asparagus, broccoli, or Brussel sprouts), will feed two people through 2-3 meals leftovers that can be used for breakfast. I occasionally add a small amount of keto-unfriendly (salsa or catsup). For breakfast, I serve a small plate of leftover Slumgullion with smoked Gouda heated in a microwave for 1 minute, which melts the Gouda over the gullion nicely.

Slumgullion:

- 1-Garlic head (chopped to medium size) or as fine as desired. The larger-sized garlic chunks are a nice surprise while eating the gullion. Garlic is good…more garlic is better! On my recent visit to Fallon, Kelli introduced me to Dorot Gardens Frozen Crushed Garlic cubes which, other than garlic from my own plantings, is now my 100% go-to for cooking.

- 1 large Onion (sweet or red), chopped to medium size

- Place garlic and onion into a large deep frying pan with Avocado oil (and a small amount of butter if desired). Start softening and browning over medium heat, stirring frequently. I no longer use any vegetable oils in my cooking and prefer Avocado oil due to its health benefits and higher smoke temperature.

- 2-8 ounce packages of sliced or whole Cremini, “baby Bella,” or portabella mushrooms. Chop these “shrooms” into smaller sizes and add to the frying pan, stirring frequently.

- 2.25 pounds of grass-fed ground Beefalo. Grass-fed ground beef may be substituted, but I have found the beefalo to be much more flavorful. Add the beefalo to the pan, chopping the meat into small chunks. Continue stirring and chopping until the beefalo is browned. Drain.

- 1-10 ounce container of Organic spinach, washed and drained. Place the drained beefalo/onion/garlic/shroom back into the frying pan and add the spinach, stirring often over medium heat. The spinach will shrivel and blend into the gullion.

- 5-extra-large pasture chicken eggs. Preferably from hormone-free, antibiotic-free, and grain-free chickens. Mix the eggs into the gullion, ensuring that the eggs are cooked through. While this is happening, additional fat from the meat or liquid from the spinach will collect. I like to leave this in the pan and in the glass refrigerator container rather than draining as this adds flavor when reheating for the next meal or breakfast.

I have added ground black pepper and recently added red pepper flakes in the early stage with the garlic and onion. It all depends on your taste and whether you can tolerate the hotter varieties of SLUMGULLION!

Enjoy,

Kelli’s dad

1 Slumgullion: Merriam-Webster (https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/slumgullion)

2 (https://sharedtastes.wordpress.com/2013/12/24/slumgullion-stew-a-historical-mystery/)

3 The Web Urbanist: https://weburbanist.com/2010/06/03/hoboglyphs-secret-transient-symbols-modern-nomad-codes/

Comment

Comments