Even if we don’t love them, a healthy garden is home to a great number of insects. They are an integral part of the full ecosystem in your yard. This year my healthy garden is hosting a few more unwelcome bugs than I care to admit. I had leaf miners show up early spring in force and now the aphids are here, and they brought all their friends. Thanks in part to social media good bug campaigns and the great work schoolteachers and nursery owners do, we all know ladybugs, lacewings and parasitoid wasps are voracious aphid eaters, we should also remember the soft-bodied insects are food for birds too. As I’m writing this, a goldfinch is having an aphid breakfast off of one of my rose bushes. In my own yard, I strive for a balance but sometimes for a whole host of reasons, things get out of whack.

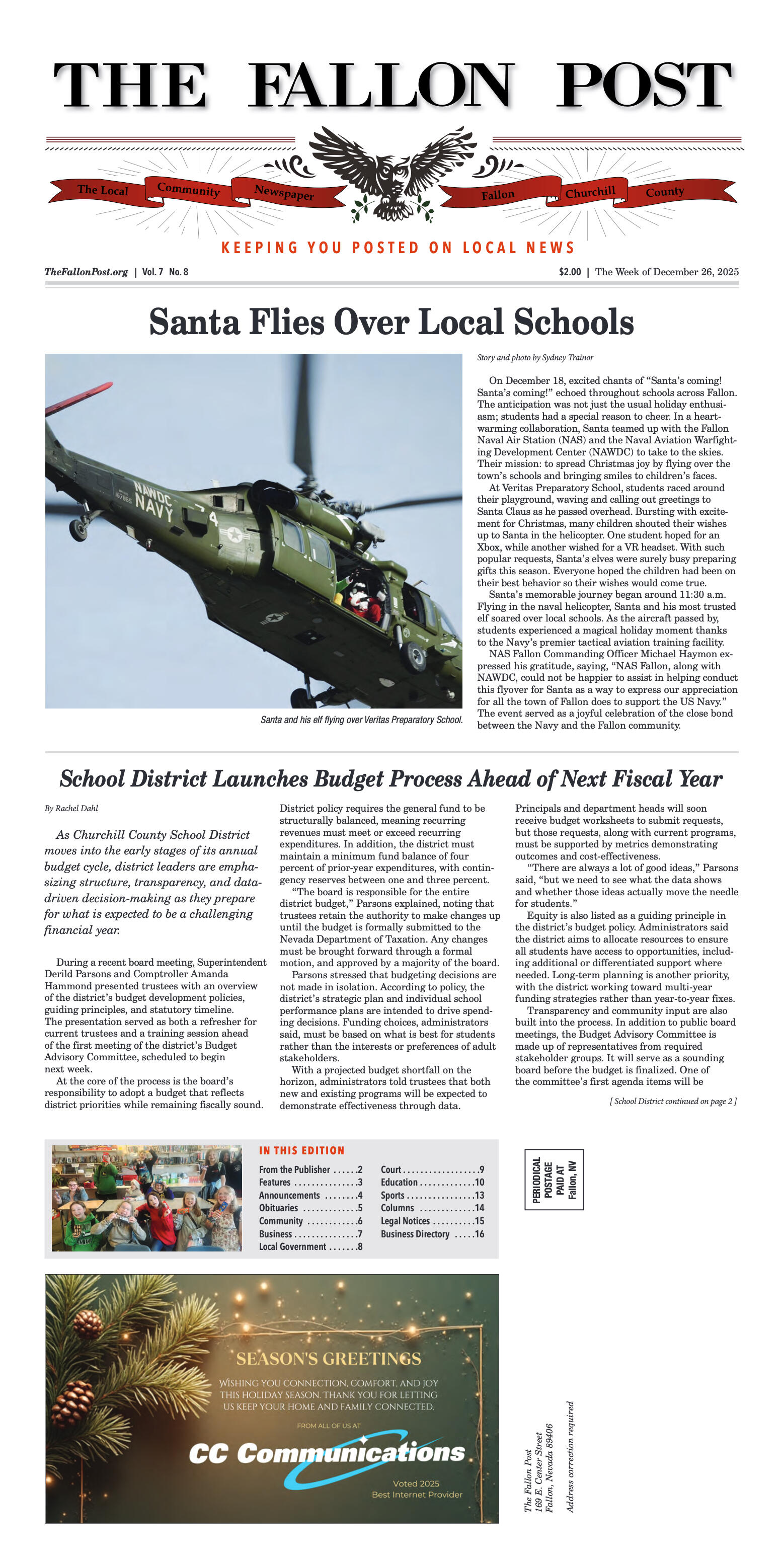

There are about 5,000 species of identified aphids. They are a successful genus; tiny sapsucker fossils have even been found preserved in ancient Baltic amber. Funny side story, there was a Royal Navy insect-class gunboat that was commissioned in 1915 called the HMS Aphis. Sister ships included no kidding, the Bee, Ladybird, and Scarab. Sometimes called plant louse or my favorite name ant cows. You might see them also called greenflies or blackflies, although they come in other colors like pink, yellow and brown as well. Then there are woolly aphids that look sort of like a small cotton ball of white fluff, you might see them between branches on your crabapple trees or especially on new shoot suckers found at the base of trees.

Woolies are one of a few hundred aphids that torment farmers and gardeners worldwide. Interestingly, these tiny bugs are found mainly in temperate zones. There are pea aphids, cabbage aphids, spruce aphids, green peach aphids, corn root aphids, potato aphids, and rose aphids to name just a few. There are several species that affect alfalfa as well, like the blue alfalfa aphid or the spotted alfalfa aphid.

Their lifecycle is complicated and frankly a little science fiction sounding. Let me share a few “highlights” from a common aphid. Stem mothers are flightless aphids that reproduce without fertilization through the summer. On a single plant, the stem mother lays many live babies (instead of eggs like many other insects). When her plant gets overcrowded, some of the sapsuckers will develop into mature adults that fly to another plant they can chow on. In late summer males and females are produced that mate and overwinter in the ground. There are even some aphids that have ant bodyguards. The ants stroke the aphids’ underbelly and collect an excreted honeydew - the shiny stuff you might see on leaves alerting you to their presence. In this mutualistic relationship, ants reportedly will even move their aphids to healthier plants. Some aphids cause galls, you might notice marble-sized round green balls that look out of place on your cottonwood leaves for example. Also on cottonwoods, a red brain shape you might notice more after autumn leaf fall is created by the poplar vagabond aphid, who also wins the best-named aphid award. Check out the USDA website and the articles on, “Petiolegall Aphids” for more exciting late-night reading. The good news is in this case, usually, the damage is only unsightly and superficial.

Aphids use piercing mouthparts to feed on the sap of the phloem vessels in many different plants. You might remember the terms, xylem, and phloem from biology class when discussing the vascular system of plants vs non-vascular plants like mosses and algae. A quick refresher, the xylem moves water and minerals up from roots and out to the leaves. Phloem takes food produced in the leaves from photosynthesis downward to roots and stems. This part of my column I should say was interrupted by a random snow shower. I ran outside and brought all my pepper and tomato starts in and now twenty minutes later it is bright and sunny again. Ah, Nevada springtime!

Aphids can cause sooty mold fungus, bacteria, and some viruses. I read some people are actually allergic to insects in large doses.

Physical controls include handpicking, pruning, and spraying. A strong stream of water can be an effective control early on in an infestation. Also, a few teaspoons of liquid dish soap mixed with a quart of water sprayed on the leaves can help as well. Pay special attention to the undersides of the leaves. You might need to do this treatment every few days for a few weeks. Nurseries sell commercial insecticidal soaps or neem if you’d rather.

Sign up to receive updates and the Friday File email notices.

Support local, independent news – subscribe to The Fallon Post, your non-profit (501c3) online news source for all things Fallon.

The Fallon Post – 2040 Reno Hwy, #385, Fallon, Nevada 89406

Comment

Comments