As we round the corner and enter the last days of Election Year 2020, we are all thinking about and wondering who will best represent us on major policy issues.

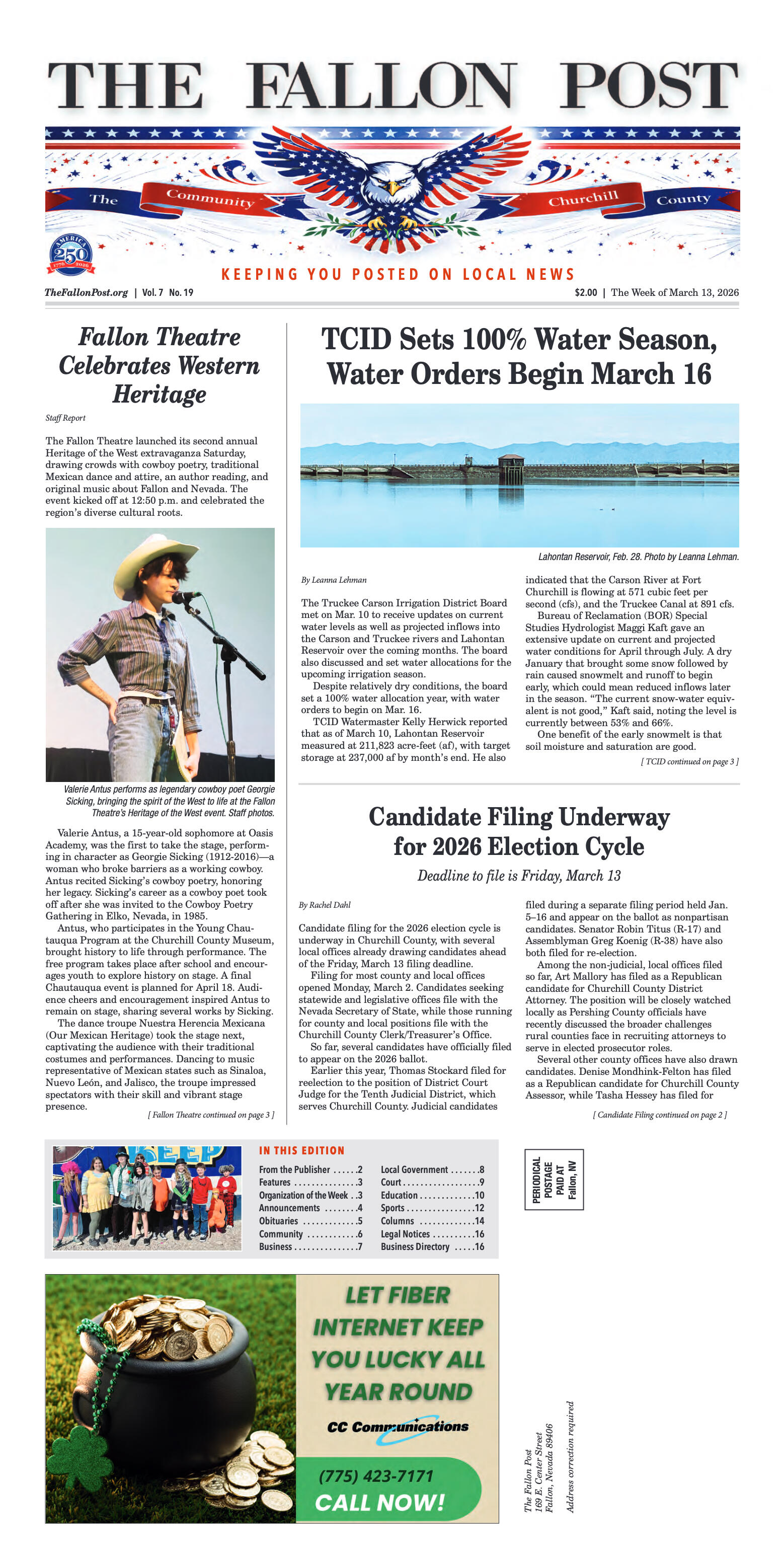

One of the more important issues is the electoral college. What is it? How does it affect me outside of election day? Since the beginning with the framing of our Constitution, many voters have had these questions and wonder today why it still exists.

The office of president is the only office where the popular vote is not the deciding factor like that of elections for governors, school boards, and judges. There are multiple political problems created by those trying to circumvent the electoral college. The more pressing of these include gerrymandering, filibuster reform, voter suppression, and negative partisanship. To fix these, there were at least six attempts to change the electoral college in the Constitution through amendments from 1804 to 2016. Historically, it is extremely difficult to gain a two-thirds vote in congress in order to pass an amendment and these ratifications never succeeded.

Public opinion polls throughout history have consistently supported these attempts at change – from a 63 percent public approval in the 1940s, 80 percent in the 1970s, and 81 percent just last November.

So, what are we continually arguing about?

A particular fight with the electoral college is the winner-take-all process. Winner-take-all is the presidential election process in most states. The winner of the most votes wins all of the electoral votes. If a candidate wins the presidential race by a single vote, they win all of the electoral votes. However, a presidential candidate winning does not mean the majority voted for them. Instead, presidential candidates must win a plurality of votes.

Earning the plurality of votes means a candidate received more votes than the losing candidates, but not an absolute majority of votes. This all means that the electoral college does not conform to the usual principle of a democracy – that one person equals one vote for a candidate.

By the 1800s, some congressmen were upset that the electoral college system was designed, “for times when the electorate was regarded as an uneducated rabble and when the communication of information took weeks or months and not seconds,” according to American Historian Alexander Keyssar.

Through the next century, negative partisanship increased along with gerrymandering. Segregation in the 1950s only continued to cement the use of the electoral college, and economic and other social minorities began to affect the election districts, with Nevada being one of the states involved.

As the country’s government grew from the 1800s to 1980s, presidential elections further encouraged a two-party system, which most voters are finding is not representing them in this year’s election.

By the 1980s, senators attempted to combat these problems by creating many amendments for what is now called the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact. The policy chooses winners from a popular vote with an absolute majority. The compact does not take effect until enough states pass the legislation to equal the 270 electoral votes a presidential candidate needs to win office.

In our contemporary time, the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact is yet to be approved -- being seventy-four electoral votes short for the policy to take effect.

Nevada’s state legislature, in both the house and senate, agreed to be a part of the compact. However, Governor Sisolak vetoed the bill saying that, “it would diminish the role of smaller states like Nevada.”

As a point of interest for the state of Nevada, many historians say that a change to a national popular vote and loss of the electoral college would eliminate ‘battleground states’ and all states would be visited. Along those lines, there is speculation that district elections give a larger voice to the diverse economic interests, including agrarian communities like Churchill County.

While the National Popular Vote Interstate Compact and other reform have not happened, negative partisanship has continued to increase as we have watched during this election cycle. Gerrymandering also is a continuous problem in both major political parties. Third-party candidates have not earned more than 18 percent of voters in a presidential election, which was during Ross Perot’s run. And it is increasingly hard to reform the electoral college because of the necessary two-thirds votes needed in congress, which is usually barred due to filibustering.

Voters in this election look for candidates who represent their policy platforms, for reforms in senators' powers (including campaign finance, term limits, and filibuster reform), and for their voice to be heard equally with other voters. It seems that these were the same requests of American voters in 1787, but nothing happened. So, overtime, we conceded to the system and followed the broken rules.

A political satirist, Hasan Minhaj, said that current voters, “can’t afford to waste [their] vote. So, you stop voting for candidates who reflect your values, and you start voting for one you think can win.”

That sounds exactly like what we are doing.

Sign up to receive updates and the Friday File email notices.

Support local, independent news – contribute to The Fallon Post, your non-profit (501c3) online news source for all things Fallon.

The Fallon Post -- 1951 W. Williams #385, Fallon, Nevada 89406

Comment

Comments