It is no stretch of the imagination to suggest Asa Kenyon was Churchill County’s first white resident. Like thousands of others, he crossed the 40-mile desert bound for California, until he reached the Carson River.

Asa Levi Kenyon was born 1830 in Rome, New York. In his youth he learned farming and blacksmithing from his father. Being ambitious and adventurous he left home at age 22, during the California Gold Rush, and became a miner in Gold Run, California.

He did well in mining, and it became a lifelong passion. With his newfound money he started speculating in livestock. After a year or so he travelled halfway back across the country to Missouri, where he began dealing in horses.

He recognized the need for his animals in the West and in 1854 he headed again towards California with his collection of horses in tow. Upon surviving the brutal 40-Mile Desert with his animals intact, he arrived at the Carson River. The spot was already a popular summer camp and Kenyon camped with 201 other emigrants.

But he then did something no one else had ever done. He stayed there. He found it a lucrative place to sell the horses, as so many emigrants lost their livestock to the desert and were willing to pay high prices to replace them on the final push to California.

He built a log home and station. This would be the birth of Ragtown and his home for the rest of his life. Though his cross-country meanderings were over, his journey would unfold into many paths. Besides a stationmaster, he would pursue stock raising, the salt/borax industry, mining claims, ranching, politics, and business with Native-Americans.

There has been debate over the years as to Kenyon’s motives. Some have said he was a humanitarian, assisting emigrants, or anyone else needing help. Others have called him an opportunist, no better than the robbers that preyed on the downtrodden voyager.

Testimonials state he hired bad men and natives to drive away arriving emigrants’ livestock. Kenyon would act as agent, charging $300-$500 to have his men go out and round up their animals. He charged high prices for fresh stock, hay, clothing, and whiskey.

A band of Paiutes once came to the station for gun caps. Kenyon offered them a box of caps for $300. When the Paiutes inquired as to why such a high price, Kenyon said, “The cap man is dead.”

“How much for the powder?” asked a Brave.

“It’s $300 a pound too,” replied Kenyon.

“Is the powder man dead?”

“No,” answered Kenyon, “but he is mighty sick!”

Emigrants had a tumultuous time crossing the waterless 40-mile desert to Ragtown. Kenyon had a cure. He went 11 miles into the desert and sunk a well; selling much needed water to the wagon trains at an exorbitant price. Thus, they were able to continue on to Ragtown and spend more money on supplies. Kenyon is accredited for saving untold lives doing this, all while making a small fortune.

However, not all of Kenyon’s actions were motivated by profit. He once went out into the desert to find a missing man. He found him near death and took him back to the station to recover, but the man died the next day. Another time, Kenyon raised and led a posse near Dayton to help hunt down a fugitive.

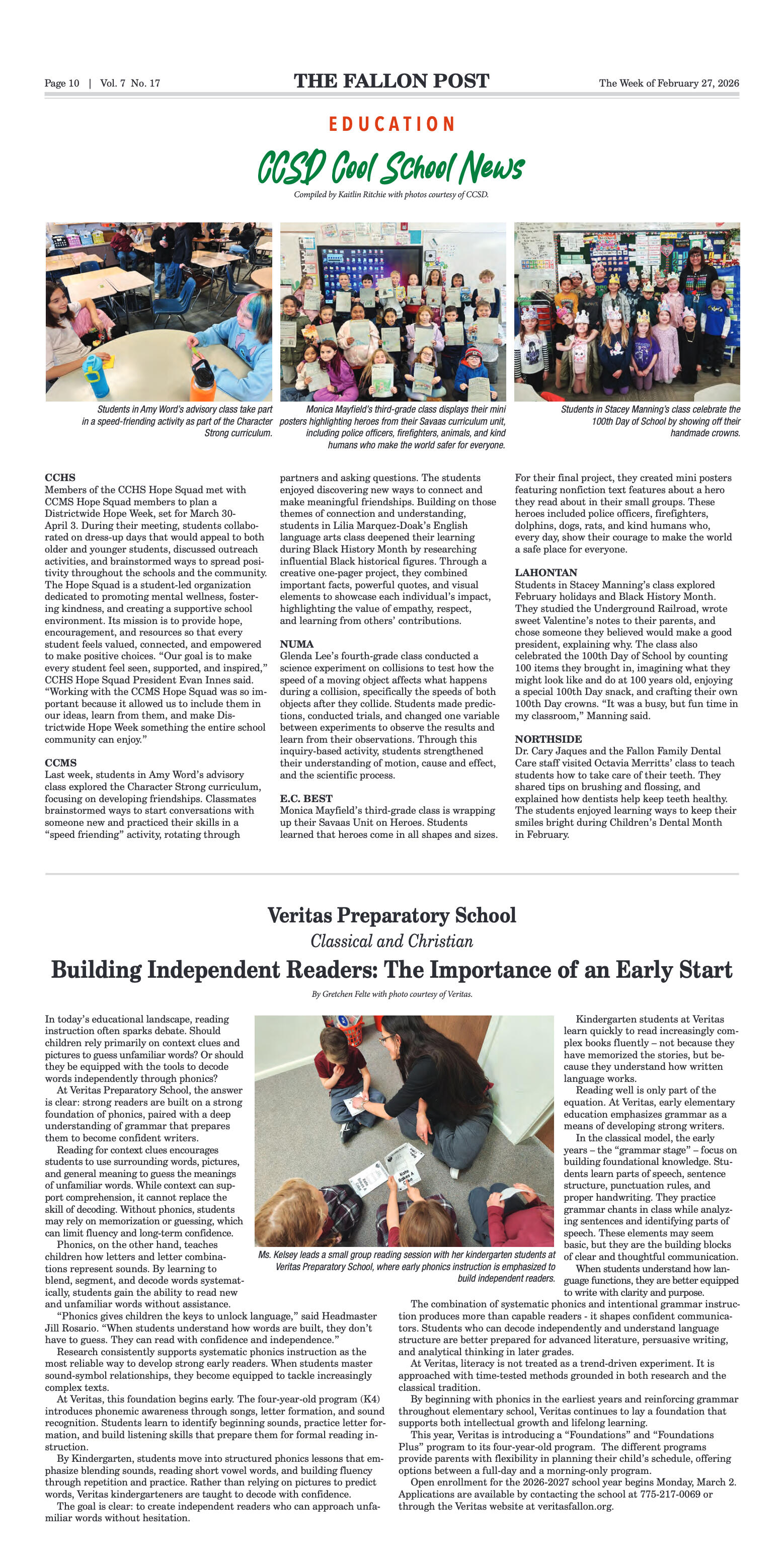

His long list of deeds run both selfless and suspicious. Ragtown Station, besides its summer fluctuation of tents, began to grow into a permanent fixture for the emigrant trek west. Mark Twain, arriving by Overland Stage in 1862, described the place as three log structures. A Post Office came and went. Kenyon’s daughter, Ida, was the first white child born in Churchill County. Within 10 years of Kenyon’s arrival, other communities sprung up along the river, such as Centerville and St. Claire.

Asa Kenyon died at Ragtown in 1884. Soon after that the area would transform into a thriving farming community called Leetevile. Kenyon’s obituary stated, “Had he been a worshiper of money he might have died a millionaire, but being a noble, kindhearted frontiersman, his home and his purse was ever open to friends or foes in distress.”

On the argument of humanitarian vs. opportunist, I tend to believe he was a bit of both. Perhaps one begot the other. Regardless of his motives, Asa Kenyon had a huge impact on the development of Churchill County. As early as the 1850’s he was advocating finding a way to harness the Carson River water, in order to irrigate and create abundant farmland.

Though he died before Fallon existed, it was in part, his vision that led to the decisions that make us what we are today.

Support local, independent news – contribute to The Fallon Post, your non-profit (501c3) online news source for all things Fallon.

Never miss the local news -- read more on The Fallon Post home page.

The Fallon Post -- 1951 W. Williams #385, Fallon, Nevada 89406

Comment

Comments